This is the second article in a series of three written by Paul Cohen in the 1990s, exploring the wave of innovation in the saxophone world that followed World War I — with a particular focus on slide saxophones.

Paul Cohen: Vintage Saxophones Revisited

Voices Of The Slide Saxophone, Part II

Innovation or gimmickry? Visionary Imusic tool or dime-store novelty? These are questions that accompany any new or unusual idea when first presented in a conservative and tradition-laden art such as music. And the slide saxophone, whose immediate practical value was not directly apparent, had a typically difficult time proving the merits of its existence. It is not clear if it ever succeeded, though it was not for lack of trying. Slide saxes were produced (if not noticed) as early as 1921 and in various forms were continually reinvented and explored through the middle 1930s. In 1928 Paul Specht presented a concert using his slide saxophone in the playing of quarter-tones. Musical Merchandise, the trade magazine, reported on this unusual event in their May, 1928 issue:

Allp photos by Hallmark Photographers, Teaneck, NJ

Specht Demonstrates Quarter-Tone Music

One of the first demonstrations of syncopated quarter-tone music ever played anywhere was presented during the program of dance and concert music played by Paul Specht and his orchestra over station WOR and the Columbia broadcasting channel. This took place on the evening of April 25th, during the Columbia Phonograph Hour under whose auspices Columbia Phonograph artists are presented weekly over a chain tie-up of seventeen radio stations from coast to coast. Specht announced the following program, consisting of his Columbia recordings: “One More Night,” “The Grass Grows Greener” “Way Down Home,” “Let a Smile be Your Umbrella,” ”We Ain’t Got Nothin’ Bess,” and a novelty recording of Southern folk songs entitled “Echoes of the South,” a brand new Broadway waltz entitled “Let’s Remember Yesterday” featuring Johnny Morris, vocalist, and the quarter-tone musical novelty was included in another new Broadway tune, entitled ‘Just a Little Different.”

Specht uses a new invention of slide saxophones with slide cornets, slide trombones, six string violins, string bass and tympani for his quarter-tone effects.

The designers of the slide saxophone differed in their intentions for the instrument. Some made an inexpensive novelty, cashing in on the popularity of the saxophone. Others may have considered the slide saxophone as

a “new sounds” instrument that would become (so they hoped) a part of the expanded sonorities heard in jazz and popular ensembles. There was a particular interest in the sounds of other cultures, particularly the Middle East and the Orient, and these sounds often found their way into popular music-making, including show music, popular music concerts, dance music, vaudeville, and other touring circuits. And, of course, the emergence of jazz often included a wealth of new sounds never before heard by most of America.

There were those who considered the slide saxophone as a new, contemporary, musical instrument that could explore, with some degree of seriousness, a new, listening experience. And why not? There were slide trombones and trumpets, stringed instruments (including the guitar and ukelele), and a host of tuneful percussion with movable tones. Experiments with the slide saxophone were conducted within existing ensembles, one of the last being Will Osborne’s band from the late 1930s.

It was not an idea taken lightly. When the instrument began to attract some popularity in the 1920s, at least one manufacturer commented on his reluctant willingness to mass produce the instrument. The manufacturer (probably Lyons and Healy) agreed to custom-make them (at great cost) if only to dissuade the purchaser from buying a foreign-made instrument. This editorial appeared in Musical Merchandise, April 1928, next to the article about the new 8-string Octofone that combined qualities of the banjo, ukelele, guitar, taro patch, tiple, mandolin, mandola, and mando-cello.

What One Manufacturer Thinks of the 1/4 Tone Saxophone

As regards the quarter-tone saxophone, I have known of this for quite some time. They have used it in Europe, but of course the instruments have to be made specially for that sort of work. They would naturally be very expensive unless made in quantity and it would be unsafe for any manufacturer to build them in quantity right off the bat, for there is a question as to how long it will take before they become actually popular. It may take many years before the country can appreciate the new scale of quarter tones.

I know that our factory could not afford to tackle this matter only by making special instruments from time to time as they are needed and the purchaser would necessar-ily have to pay the price. I believe every other manufacturer in this country is in the same position as ourselves, so we feel we have an even break with the rest of them. But, it is not necessary to send abroad for any specially made instrument of that character. If they want them, we can make them.

THE KING C SAXOPRANO

A few years after the introduction of the Reiffel & Husted Royal Slide Saxophone (see part I of this series in July/ August 1994 Saxophone Journal) the H. N. White company produced their slide saxophone, the King C Saxoprano (see PHOTO 1). This simple yet ingenious little instrument consists of a conical tube with a slit or opening that extends down most of its length and into the actual tube. Suspended just above the opening is a leather strap, held in place by an adjustable fastener. Different pitches are produced by pushing down on the strap at varying points on the tube. The lower on the strap one pushes, the longer is the tubing length closed and the lower the tone. Sliding one (or two) fingers up and down the strap slides the tone quite smoothly. The H. N. White Company added a bell at the end of the tube to give a saxophonic appearance, (PHOTO 3 – The French MelloSax, 1929. Shown without strap to illustrate the tuning slot and rails as well as an on the tube.) octave key to assist in a two octave (or more) range. Its range extends down to middle C on the piano. Letter names of notes are imprinted on the leather strap, assisting the well-tempered player in finding actual pitches. This works if the leather strap neither stretches or shrinks. The strap on my instrument has stretched over the years, making my slide saxophone out of tune. It is not clear how successful this instrument became in the 1920s. Despite its quality design and workmanship, the instrument was not advertised or promoted by the company, perhaps considered only as a novelty.

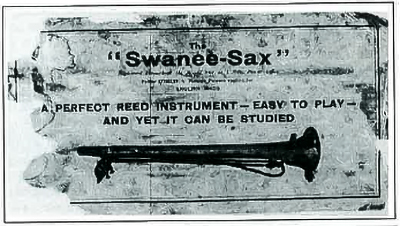

THE ENGLISH SWANEE SAX

In 1927, the English company, Swanee, produced a set of slide saxophones (PHoTO 2). The smaller Swanee Sax has a low range to Bb below middle C, while the taller of the two extends down to F below middle C. These instruments are built on the same principal as the King C Saxoprano, with a straight conical tube pierced by a slit down its length. Within the tube is a thin metal bar whose width covers the width of the slit. A handle is attached to the bar allowing the player to move the bar up or down. The bar rises above the tube length when tones higher than the lowest pitch are played. The mouthpiece is attached to a small tube that enters into the side of the instrument, leaving the top of the instrument for the rise and fall of the metal tuning bar. The company, no doubt, had high expectations for their creation. In an advertisement for the instrument (Fig 1) the Swanee-Sax was touted as “A perfect reed instrument, easy to play, and yet it can be studied.” The instruction manual that came with the horn (a one-page piece of paper) concerned itself with reed care and handling.

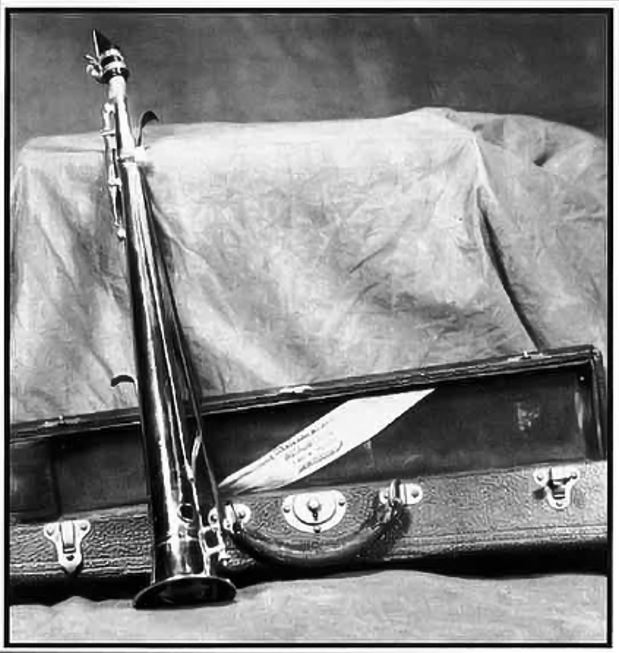

THE FRENCH MELLOSAX

PHOTO 3 – The French MelloSax, 1929. Shown without strap to illustrate the tuning slot and rails on the tube.

Rene Lazare and William Clapham of France were awarded a patent in 1929 for their slide saxophone (Photo 4). Called the MelloSax, it closely follows the King design, but with significant enhancements. It was longer, to the length of a conventional Bb soprano, and the strap-slide mechanism was improved to allow a surer seal over the tube opening. The strap could be made of rubber or other supple material and it fit over rails that paralleled the tube opening. The strap was pushed into place not by fingers, but by a bar operated by the lower hand. I do not know how popular it was in France, but the available literature for the MelloSax might be some indication as to its reception and acceptance in Europe.

As remarkable as the King C Saxoprano, Swanee-Sax and MelloSax are, they pale in comparison to several instruments that were hand made in limited, prototype quantities. The amazing, circular slide, alto saxophone and the fully chromatic slide, straight, alto saxophone will be explored in “Voices of the Slide Saxophone III – Those that Might Have Been,” the final installment in this series.

My thanks go to Dean of Hallmark Photographers in Teaneck, New Jersey, for his terrific pictures of the slide saxophones.

Afterword and Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to Dr. Paul Cohen for both writing this remarkable article series and generously granting us permission to republish it. His dedication to uncovering and preserving the history of saxophone innovation is truly inspiring, and we are honored to help make his work more accessible to a wider audience.

For those who wish to explore more of Paul Cohen’s work, we highly recommend the following resources:

PC Readers, CD web page: https://www.ravellorecords.

com/artists/paul-cohen/

YouTube channel: https://www.youtube.com/@

paulcohen2556 Publisher website: https://totheforepublishers.

com

We hope this article inspires the same sense of wonder and curiosity in you as it did in us.