This is the third article in a series of three written by Paul Cohen in the 1990s, exploring the wave of innovation in the saxophone world that followed World War I — with a particular focus on slide saxophones.

Paul Cohen: Vintage Saxophones Revisited

Voices Of The Slide Saxophone, Part III

Those That Might Have Been!

Innovation or gimmickry? Visionary music tool or dime-store novelty? There were certainly elements of both in the thought and use of the slide saxophone, in some ways paralleling the development of the conventional saxophone in this century. The foundation of the saxophone tone, which is dark, smooth, and lyrical, was still the predominant tone quality in the 1920s and 1930s.

Despite the rise of new and vibrant musical mediums in the 1920s that included the saxophone, the instrument still maintained an essentially lyric tone, sharing many qualities both acoustically and stylistically, with the human voice. It is a characteristic that was constantly celebrated and sought out in classical and popular music of the time. The excavated chamber, high baffle, and close lay of the mouthpieces, combined with the moisture-resistant bore design of the instrument, cannot help but offer such tone. It is possible that designers sought to combine this inherent lyricism with the qualities most associated with the voice, especially that of portamento, the subtle slide between two notes so idiomatic of singing and emotional expression.

Parts I & II of Voices Of The Slide Saxophone examined the Royal Slide Saxophone, the C Saxoprano, the Swanee-Sax and Mellosax. These instruments were commercially produced and mass marketed. As it turns out, these were all soprano models. Slide altos and tenors were not only designed, but produced in very small numbers, as prototypes. This final installment looks at designs and prototypes of slide saxophones that were never made but might have been — Those that might have been.

THE SLIDE TENOR

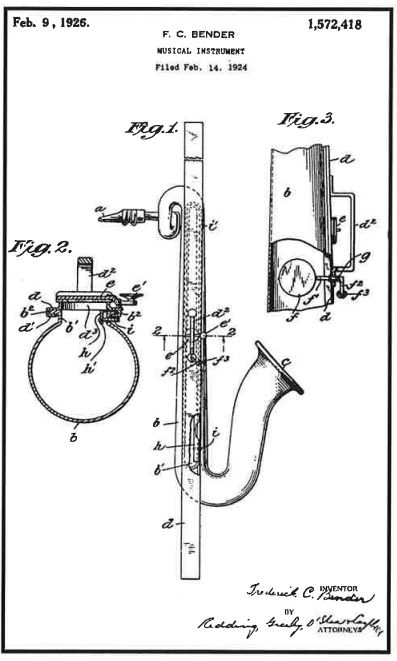

In 1926 Mr. F. C. Bender from Long Island received a patent for a slide saxophone based on the principal of the Reiffel & Husted Royal Slide Saxophone. Within a saxophone-like shaped tubing, a long slit is covered by a rod that is moved up and down. As the rod is lowered, more of the tubing is closed, lowering the pitch. Mr. Bender conceived of the instrument as early as 1924, and it was intended for lower voices than the soprano. His was based on a tenor (perhaps baritone) design (Example 1). The logistics are formidable, the image limited, and the playing undoubtedly awkward. But the idea of the instrument is bold, daring, and innovative, a testament to the spirited individualism and character of the times. It is not known if any were built.

THE STRAIGHT SLIDE ALTO SAXOPHONE

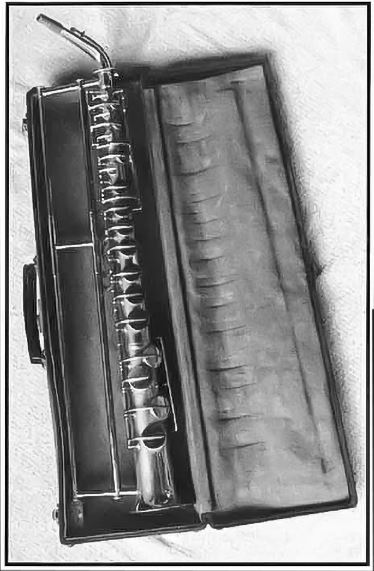

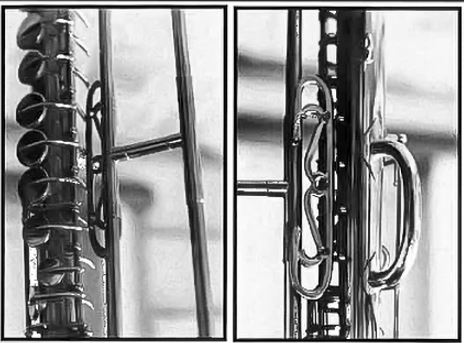

This is an improbability taken to new heights. Combining the shape of a straight alto with the notion of a slide while preserving the pads, keys, and mechanics of a conventional saxophone is fantasy slightly beyond the beaten path. Some anonymous, but brilliant, designer thought enough of the idea to create such a saxophone. This instrument, in the collection of the well-known instrument collector Richard Hurlburt of Massachusetts, is remarkable in its authenticity and workmanship (Examples 2, 3, 4). There is no name. Mr. Hurlburt told me that it was European in origin and there were probably less than ten made. It does not appear to be a modification of an existing conventional alto, but an entirely new design based on tone holes, keys, and pads. The degree or quality of the glissando between pitches is a function of the curvature of the cam and the height of the key levers. It is a remarkable, bizarre instrument, reminding me of the axiom I have learned in my years of researching and collecting. In the saxophone world, if you wish for something hard enough it usually appears. But then it will never go away.

THE CIRCULAR SLIDE ALTO SAXOPHONE

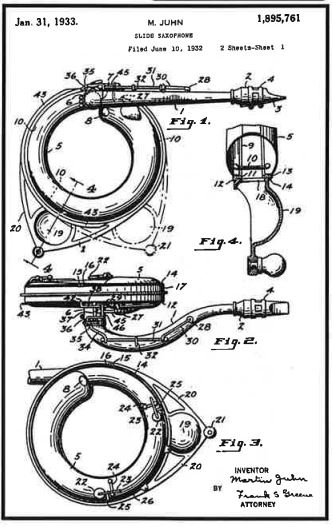

Given the awkwardness of playing a straight slide saxophone, the obvious ergonomic improvement would be to make it circular. Incredibly enough, the circular alto saxophone was made in Cleveland, Ohio, by Martin Juhn in the 1930s. I first was introduced to the instrument through a patent from 1933 that described and sketched this remarkable and intricate horn. It was not clear from the patent if any were actually made:

Example 5: Patent sketch of the circular slide saxophone by Martin Juhn from 1932.

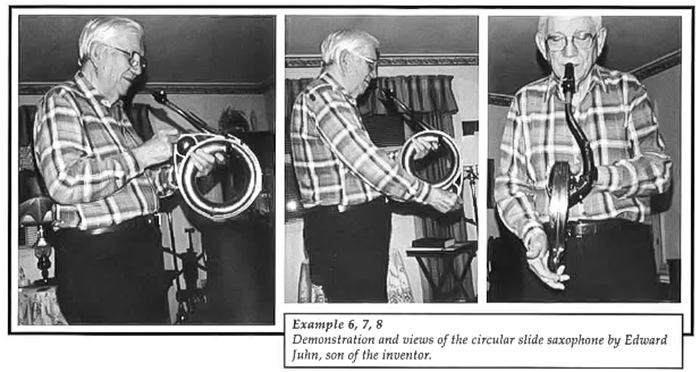

With a little detective work, I found his son, who owns one of the instruments. I had the pleasure of visiting Edward Juhn and his wife Helen, last spring. They graciously allowed me to play this exceptional instrument and learn about the inventor. One has to hold and play this slide saxophone to fully appreciate its tone and innovative qualities:

It is based on a long, conical tube with an opening in the middle running from top to bottom. On top is a thinner circular metal section that revolves around the top, covering and uncovering the opening. There is a handle attachment that easily facilitates both the rotating motion and the torque of the extension. In addition to a normal octave key, this amazing mechanism incorporates an automatic octave key system, which allows for a seamless and uninterrupted slide through the higher register above written G#! I played the horn for about an hour during my visit. The sound is full, rich, and direct. It was a unique tonal combination of a lyrical curved alto with the more tonally than the forthright straight alto. And, of course, there was a seamless connection between pitches. The action of the sliding mechanism proved surprising. I expected a herky-jerky movement from the unusual circular motion required to slide around the circumference. Instead, I experienced an elegant, gliding motion that allowed surprising control and comfort. With a little practice, one could actually play the horn. Its range easily extends from low Bb up to high D and, with some overtone technique, I could bring it up an additional octave.

The inventor, Martin Juhn (1885–1975), is one of many unknown brilliant designers and inventors. Born in Europe in 1885, he moved to Cleveland in the early part of the century. Originally a wood carver in Europe, he became a pattern maker (for casting) in the United States. He was a proficient player on flute, clarinet, and saxophone and was involved in a remarkable number of projects and jobs throughout his lifetime. In addition to his own shop, he worked for the Wershing Organ Company (from Cleveland!) restoring organs and for Henry Ford in Detroit with the automobile industry. In his shop he not only designed the circular slide saxophone, but made and sold his own clarinet and saxophone reeds. Edward told me that he worked for years on the design of the saxophone and made as many as six, none of which were commercially sold, although he did try to interest various jazz and commercial bands (including Will Osborne’s bands in the early 1940s). Unfortunately, it was too daunting a prospect, even for those ensembles that experimented with new sounds and instruments.

Of the many rare and unusual saxophones that I have played and performed on, the circular slide alto saxophone of Martin Juhn is one of the most remarkable, amazing, and, of course, least practical, instruments. Practical application aside, it is truly a wonder.

A ROYAL SLIDE SAXOPHONE POSTSCRIPT

Since Part I of my slide saxophone series was written, I was introduced to another instrument so similar to the Royal Slide Saxophone that it might be considered its close cousin. The firm that produced this Royal Slide Saxophone, Reiffel & Husted, began as a silversmith company in downtown Chicago, c. 1911. The World War I demand for military instruments, especially that of bugles, led Reiffel & Husted to the successful production first of bugles (c. 1918) and then to cornets and trumpets in different keys, as well as trombones and other brass instruments.

In 1922 Carl Reiffel contacted Lyon and Healy, also based in Chicago, about distributing his new invention, the slide saxophone. At the time Lyon and Healy was a huge musical merchandising firm. In addition to selling a full line of saxophones with the Lyon and Healy name (made by other manufacturers), they sold a novelty 1/2 curved soprano which they touted as being of perfect “balanced action.” It was designed to compete with the King Saxello. The response from Lyon and Healy in 1922 was not encouraging. According to the article on Reiffel & Husted by Lloyd P. Farrar that appeared in the February 1991 issue of the AMIS Newsletter, the company wrote back: “If you succeed in making the slide saxophone work to our satisfaction, we are willing to authorize your firm to manufacture these instruments for us. Any new features you embody in same are to be exclusively our property. Patent applications are to be assigned to us by you without charge.”

Not surprisingly, Carl Reiffel immediately applied for his own patent, which was granted on June 24, 1924. By then the instrument was in production, advertised, and available for sale.

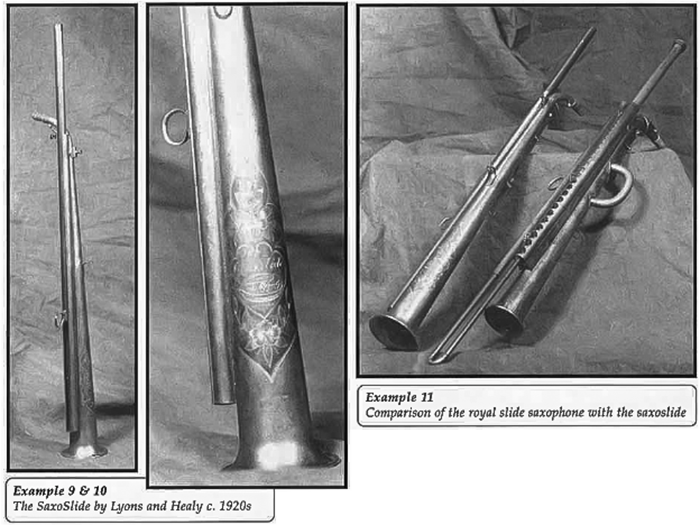

It seems that Lyon and Healy’s interest in the Royal Slide Saxophone did not end with this less than magnanimous (and quickly rejected) offer. Soon after, they came out with their own instrument, the SaxoSlide (Example 9, 10, 11). Musical Merchandise gave it a rather whimsical introduction. It captioned the picture “The latest Misery Maker” and went on to describe the instrument:

“This peculiar looking object is neither a walking stick nor a leg of mutton. It is merely the latest form of the saxophone produced by a Chicago firm. It is keyless, except for the single trill key operated with the thumb of the left hand. The variation in pitch is produced as in a trombone by slots in the bore, with a slide control operated by a ring through which the player passes the forefinger of his right hand. Certain scoops and yowls of the familiar instrument become even more terrifying in this new one.”

Based on the design of the Royal Slide Saxophone, the SaxoSlide is a simplified version, without the largely ornamental trombone-like slide and sporting a redesigned octave mechanism, an engraved bell, and different handle and thumb rests. The instrument that is pictured belongs to clarinetist Ray Wheeler of New York City. His grandfather purchased the instrument in the 1920s and played it for over sixty years (along with conventional woodwinds) in a wide assortment of popular and social engagements. It is not clear if Lyon and Healy contracted Reiffel & Husted to supply these instruments or whether they appropriated just enough of the original design to produce their own in version without a patent infringement. Certainly, a few were sold. In addition to Mr. Wheeler’s, Rob, a member of the Disneyland Side Street Strutters Jazz Band from California, also has one, as do others.

I am reminded of another noble experiment with a new instrument designed to emulate the qualities of the human voice. The Theremin, an electrical instrument from the late 1920s, was a device that used the new discovery of radio waves as a basis of tone generation and control. The instrument was comprised of a base unit and two antenna separated by several feet. In between the antenna, the performer stood in a studied, almost dance-like pose. Sound was controlled by the arm, hand, and body movements of the performer, who literally sculpted inflections that created pitches, slides and phrases of great beauty. This unusual instrument, created by the Russian Leon Theremin (who died last year at age ninetyseven), was taken seriously at first. RCA Victor manufactured them for a brief time in the 1920s and composers wrote serious music, including solo concerti, which was performed with symphony orchestras. The saxophone and the Theremin did meet on at least one occassion. The Cleveland Orchestra on December 3, 1929, in Carnegie Hall, New York City, presented a concert of orchestra music that included saxophones and featured the Theremin. With Nikola Sokoloff conducting, the orchestra performed Overture For A Don Quixote by Jean Rivier (alto saxophone) and New Year’s Eve In New York by Werner Janssen (two altos and a tenor saxophone). In addition, the Theremin was featured in the First Airphonic Suite, Op. 21 by the famous American composer of the time, Joseph Schillinger.

Perhaps it was inevitable that these two instruments, both striving for acceptance with similarly vocal attributes, should meet in the symphony hall. It is a bit wistful to think, with no less provocative an imagination, that the same creativity, ingenuity, and artistic drive that produced the Theremin might also have inspired the more serious of the slide saxophones. For today’s music making, the slide saxophone can symbolize those unfound, musical attributes still inherent in the contemporary saxophone and, more importantly, in the mind and artistry of the saxophone player. We might not play the slide saxophone any more, but we can still learn a great deal about our own music-making and tonal legacy from their creation over seventy years ago.

Afterword and Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to Dr. Paul Cohen for both writing this remarkable article series and generously granting us permission to republish it. His dedication to uncovering and preserving the history of saxophone innovation is truly inspiring, and we are honored to help make his work more accessible to a wider audience.

For those who wish to explore more of Paul Cohen’s work, we highly recommend the following resources:

PC Readers, CD web page: https://www.ravellorecords.com/artists/paul-cohen/

YouTube channel: https://www.youtube.com/@paulcohen2556

Publisher website: https://totheforepublishers.com

We hope this article inspires the same sense of wonder and curiosity in you as it did in us.